INTRODUCTION

CLIENT:

Carnegie Museum of Natural History

BRIEF:

Design an interaction for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

SOLO PROJECT

TIMEFRAME:

5 weeks

COURSE:

Interaction Design Studio (MDes), Carnegie Mellon University. Taught by Mark Baskinger and Kyuha Shim

TOOLS:

invision / illustrator / photoshop / after effects

LINK TO PROCESS DOCUMENTATION

The final project for the Interaction Design Studio course was entirely open-ended, to the extent we were asked to write our own project briefs. Our only directive was that our interaction design solution had to relate to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) somehow. For our introduction to the project, we visited the museum and met with three museum employees, who gave us a tour of their newest exhibit called "We are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene." The Anthropocene marks the epoch of significant human impact on the environment, indicating that human activity has significantly altered the geological makeup of the planet. As the only exhibit of its kind in North America, it is an important step for the Museum in tackling the topic of human-caused climate change. Because this was significant for the museum and a personal interest of mine as well, I decided to focus on this particular exhibit for my project.

Though the exhibit does an excellent job of demonstrating the profound and long-lasting effects of human activity, it does not take a strong stance on humans as actants. Acknowledgement of our personal contribution and a recognition that we can do something about it are both needed to trigger behavior change on an individual level. Thus, communicating both accountability and agency became the most important part of this exploration.

MY PROJECT BRIEF

To explore the potential for a supplementary interactive system to the We Are Nature exhibit that communicates human’s role and agency in the Anthropocene and sparks behavior change.

PROBLEM DEFINITION

Though multinational corporations play their role in contribution to the destruction of the environment, we each individually perpetuate those damaging practices through our consumer culture; our dollars fuel the continuous destruction of the Earth. In my view, changing consumer behavior is the single most powerful thing an individual can do to halt the negative effects of the Anthropocene. For this reason, I decided to communicate ideas of accountability and agency through everyday consumer objects, namely a spoon.

CRITERIA

REQUIREMENTS

As I was designing for a longstanding institution, for my project requirements, I looked to the CMNH’s strategic plan. I read through the entire plan and highlighted points that reflected the museum’s content and their goals for the future. I then compiled all of this into buckets, and kept these as a guide for myself. Ultimately, some rose in priority. Here is the final list of all my requirements. All except the first two are based on the Strategic Plan:

Supplement the We Are Nature exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Communicate a sense of agency and accountability

Communicate the unity and interdependence of humanity and nature

Appeal to a range of age groups

Incorporate a multi-disciplinary approach to the study of the Anthropocene

Connect to “meaningful synergy between natural history, cultural history, and artistic endeavor”

Extend beyond the walls of the museum

“Focus on issues of direct social impact”

“Maximize relevance of content to research and public interest”

“Expose people to new experiences and explore the natural world in a rich, immersive environment.”

Provide spaces for reflection, experimentation, inspiration, creativity, and enjoyment

Keeping in mind these requirements and my focus on consumerism, I formulated primary and secondary objectives for the project.

PRIMARY GOALS

Convey a sense of agency and responsibility

Encourage people to evaluate their consumption habits

Educate and inform visitors about objects, consumer behavior, and the consequences of those behaviors

Bring awareness to the historic and multi-generational impact of our consumer habits

Appeal to all age groups

SECONDARY GOALS

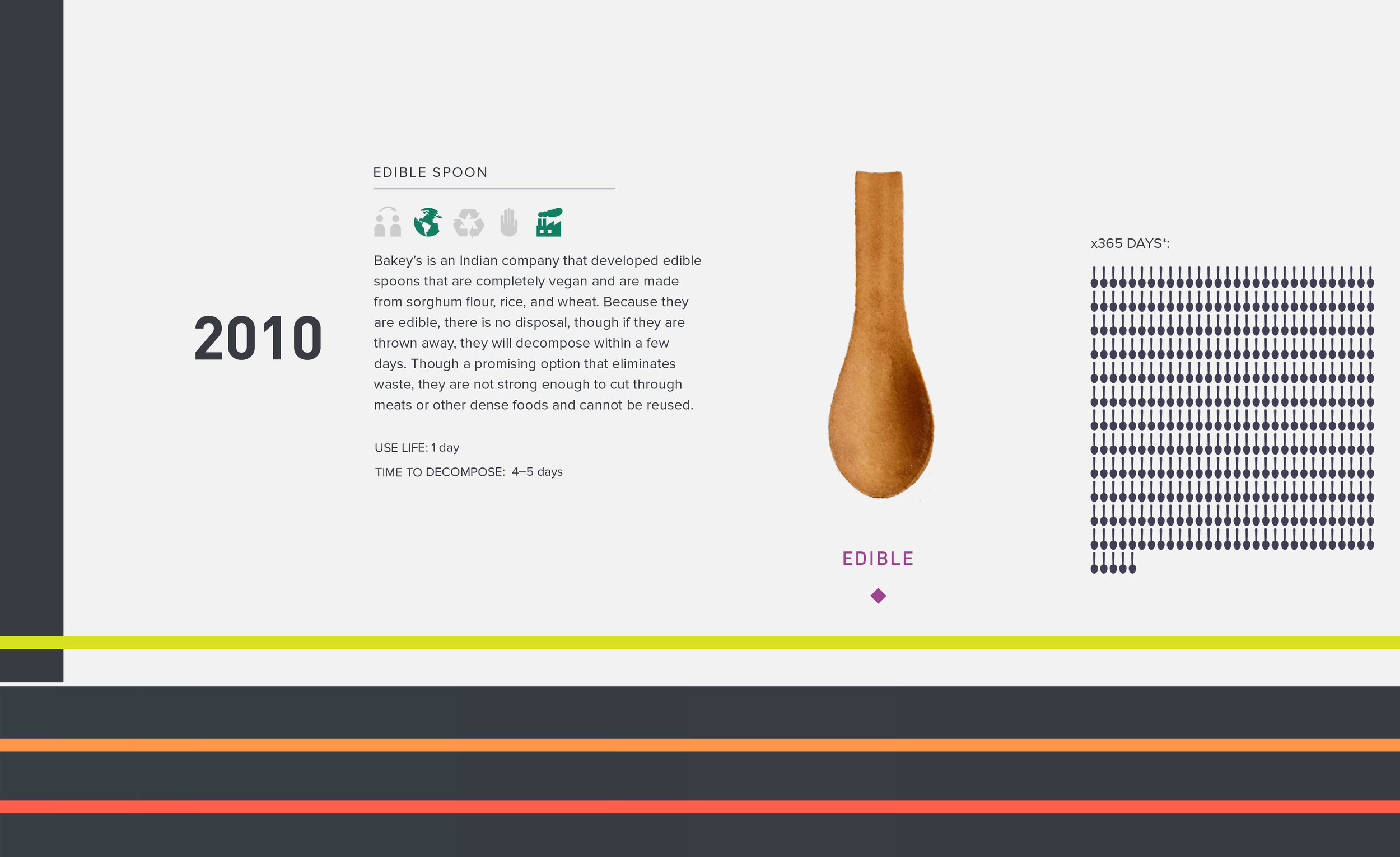

Present alternatives and spark interest in new technologies

Bring awareness to the relevance of ancient, more holistic practices and attitudes towards the earth

Educate about the sometimes destructive practices of material extraction, production, and disposal on the earth

Communicate d ifferent approaches and philosophies of human’s relationship to nature

TARGET USER

Target users are visitors to the CMNH and its website. The exhibit curators indicated that their target market for the We Are Nature exhibit was millennials, and this was strongly reflected in their visual style, language, and integration of social media trends. However, because this a topic that impacts people of all age groups, I wanted to appeal to millennials in addition to a much broader age range and breadth of education levels, so that the interaction is engaging for a range of people.

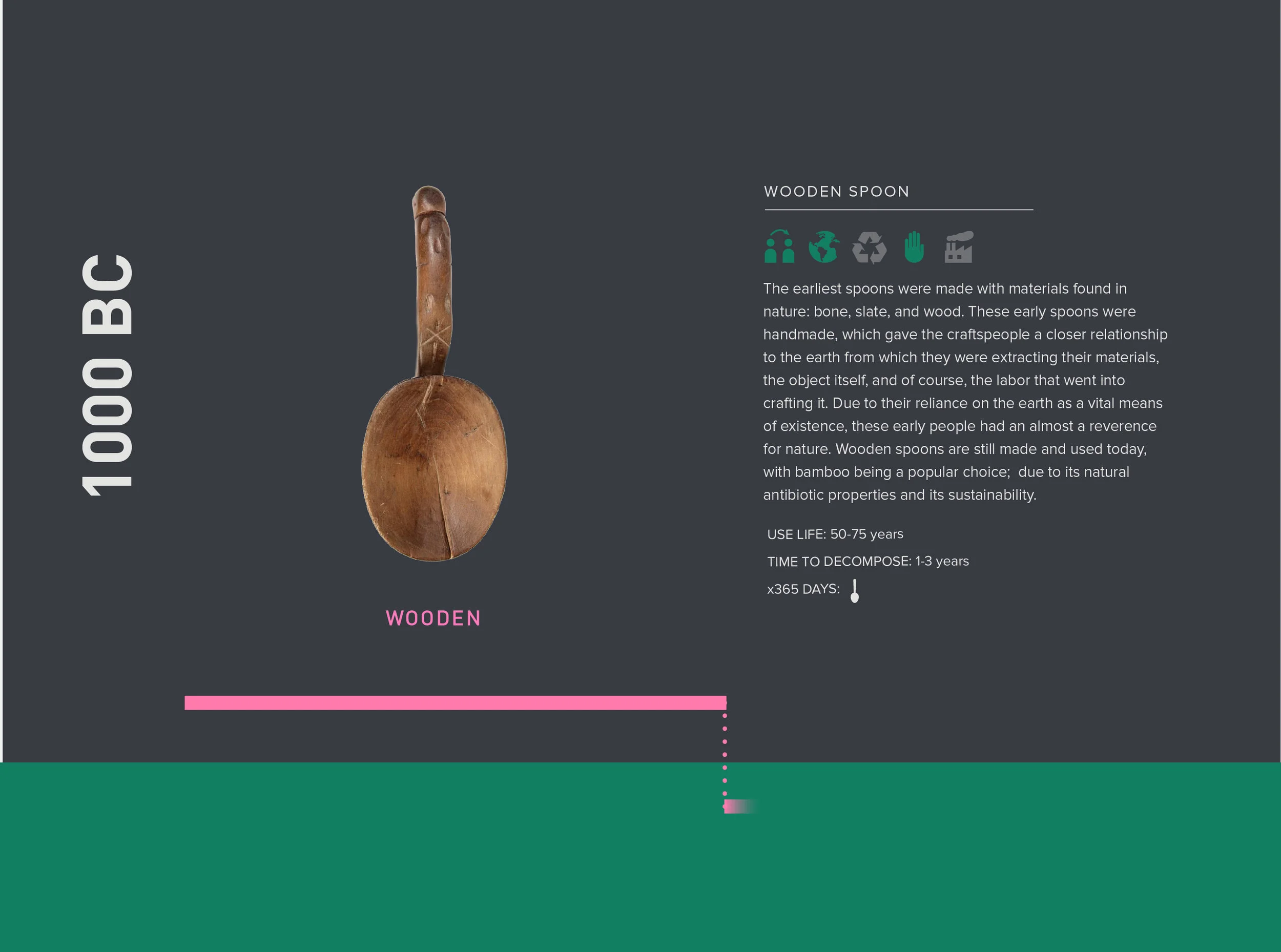

INITIAL CONCEPT

When reflecting on this project, my mind kept returning to The Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. By highlighting First Nations (indigenous) artifacts, they communicated not only a relevance to indigenous cultures and practices, but to the inherent value of nature itself. In one exhibit, they had first-person reflections of contemporary First Nations people on ancient artifacts, which communicated the reverence these people have for the earth and for others as part of a collective community. I thought it was interesting to look at the relationship of nature through the objects these people were using. This was a starting point for me, and I decided to look at the Anthropocene through the lens of an everyday object, namely a spoon.

RESEARCH & IMPLICATIONS

My research took place throughout the course of the project and helped develop, shape, and refine my concept as I went along. The majority of research came through a series of conversations with people about my project. I spoke to my instructors; Dr. Noah Theriault, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Carnegie Mellon University; and PhD students in the School of Design, Ahmed Ansari and Francis Carter.

Although not everything that was discussed with these experts explicitly made it into my final product, every conversation influenced the design decisions somehow.

Reading the Strategic Plan of the CMNH also guided a lot of my decisions. For example, they state that they wish to incorporate a multi-disciplinary approach to the study of the Anthropocene, so I approached this from a historical, anthropological, scientific, and design perspective, including different aspects of all four disciplines in the timeline. When speaking with Mandi Lyon from CMNH, she mentioned that the museum wanted to expand beyond their walls, which convinced me to make this an online exhibit rather than a physical one in the museum itself (although it would work in the “Future Thinking Lab” segment of the exhibit just as well).

Regarding materiality itself, I was exposed to the breadth of topics that need to be considered when talking about consumerism, how we produce, and how we dispose of objects. Although there were many aspects I would have liked to include but could not, every additional layer of information that I was exposed to added depth to the final product.

Speaking to Ahmed Ansari made me think about the history of the Anthropocene, which directly influenced the timeline aspect of the solution. I was also forced to think about how culture and cosmology tie in to the Anthropocene, and how closeness to nature and the material sources greatly influences our regard for nature and the objects themselves. From this, I tried to communicate aspects of consumer- and throwaway culture, and how that influences our regard for objects.

By this point I had formulated the concept of looking at the development of a spoon over time—from the earliest spoons in existence to the modern spoons such as compostable and disposable spoons. I wanted to look at different aspects of how these spoons were produced, used, and disposed of over the course of history.

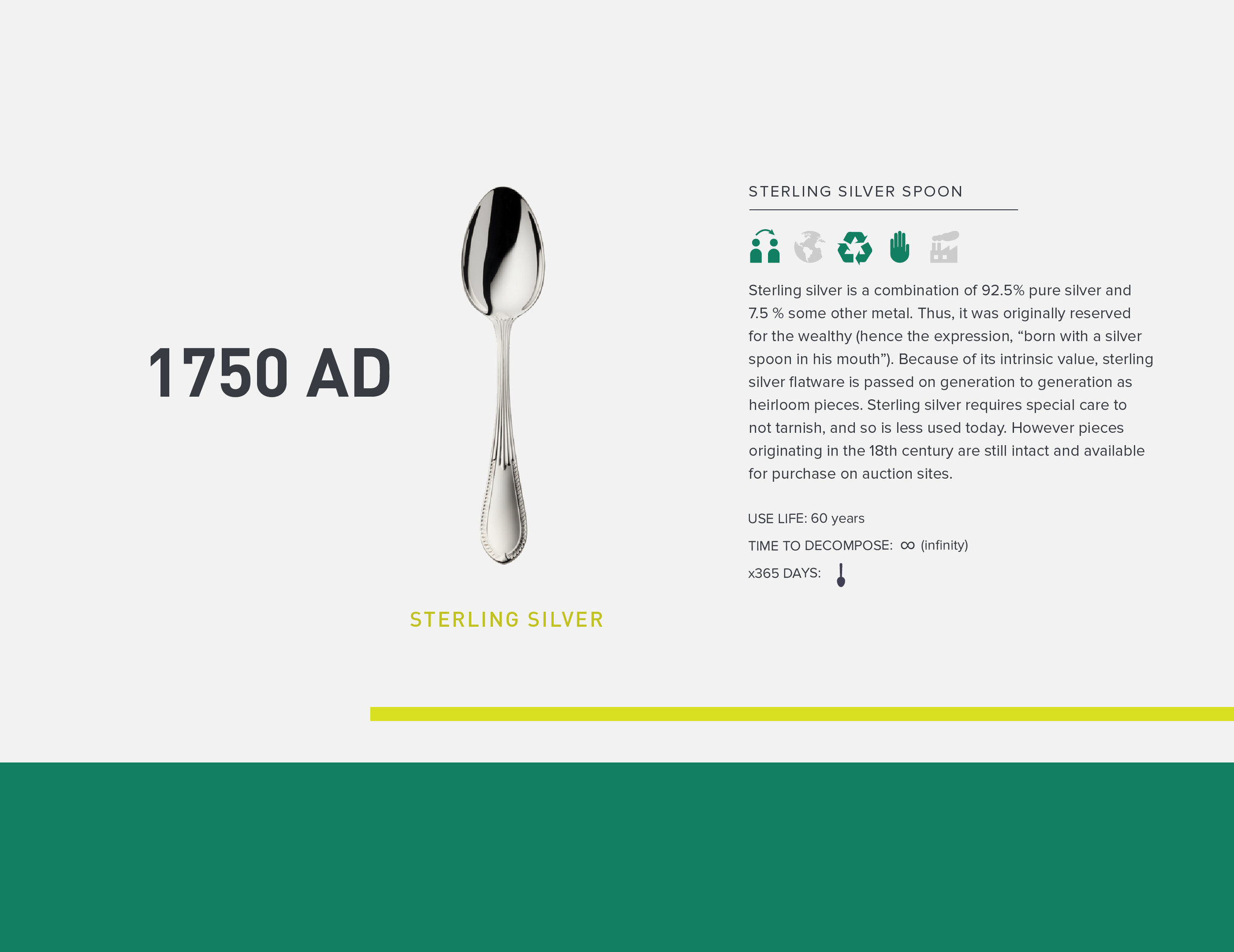

I discussed this concept with Dr. Theriault, and from him I learned about alienation from land and labor, which directed my decision to include handmade and factory-made icons as a metric for the spoons in the timeline. He also talked about the issue of accountability, which influenced the theme of my project (agency and accountability).

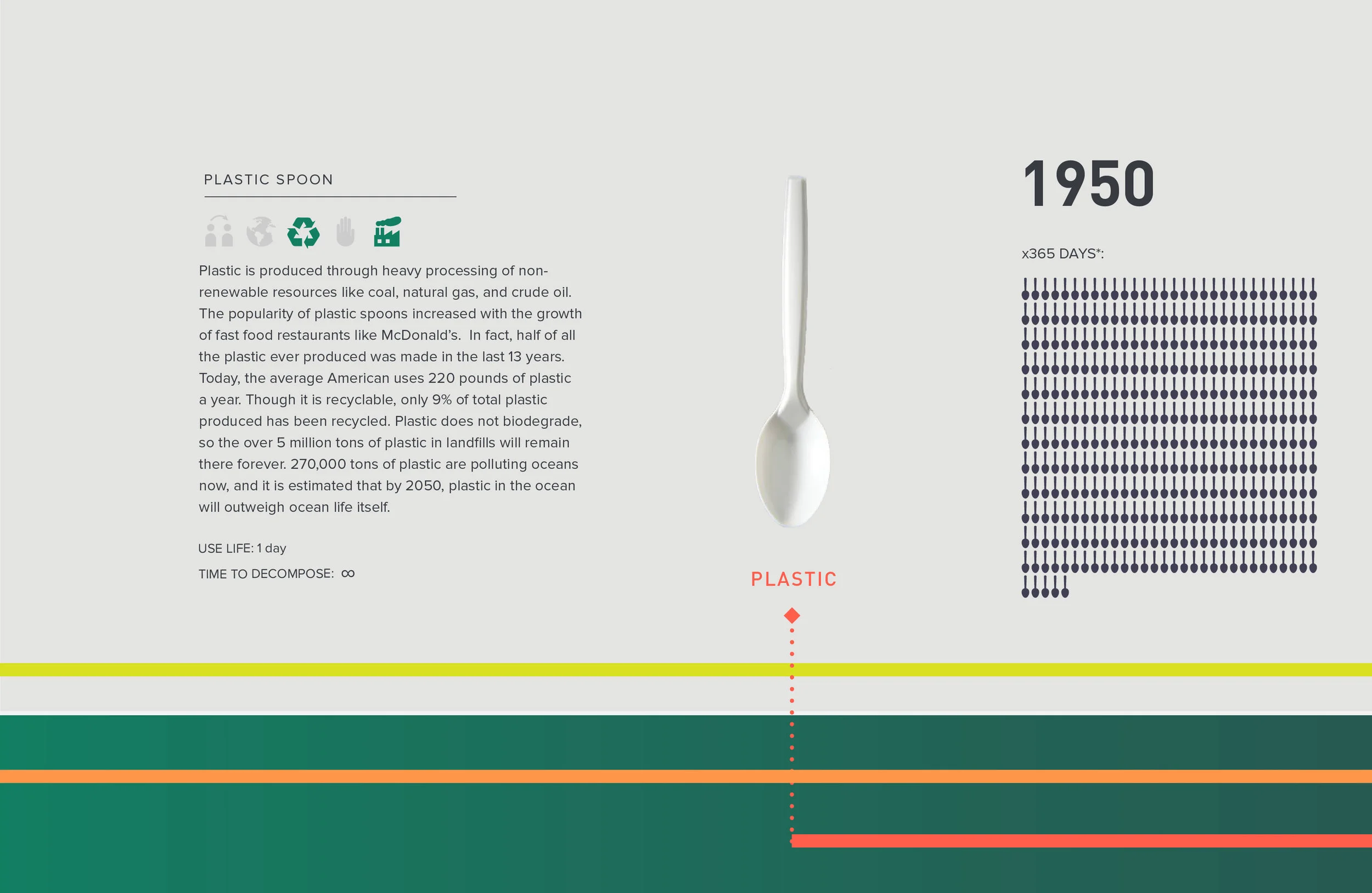

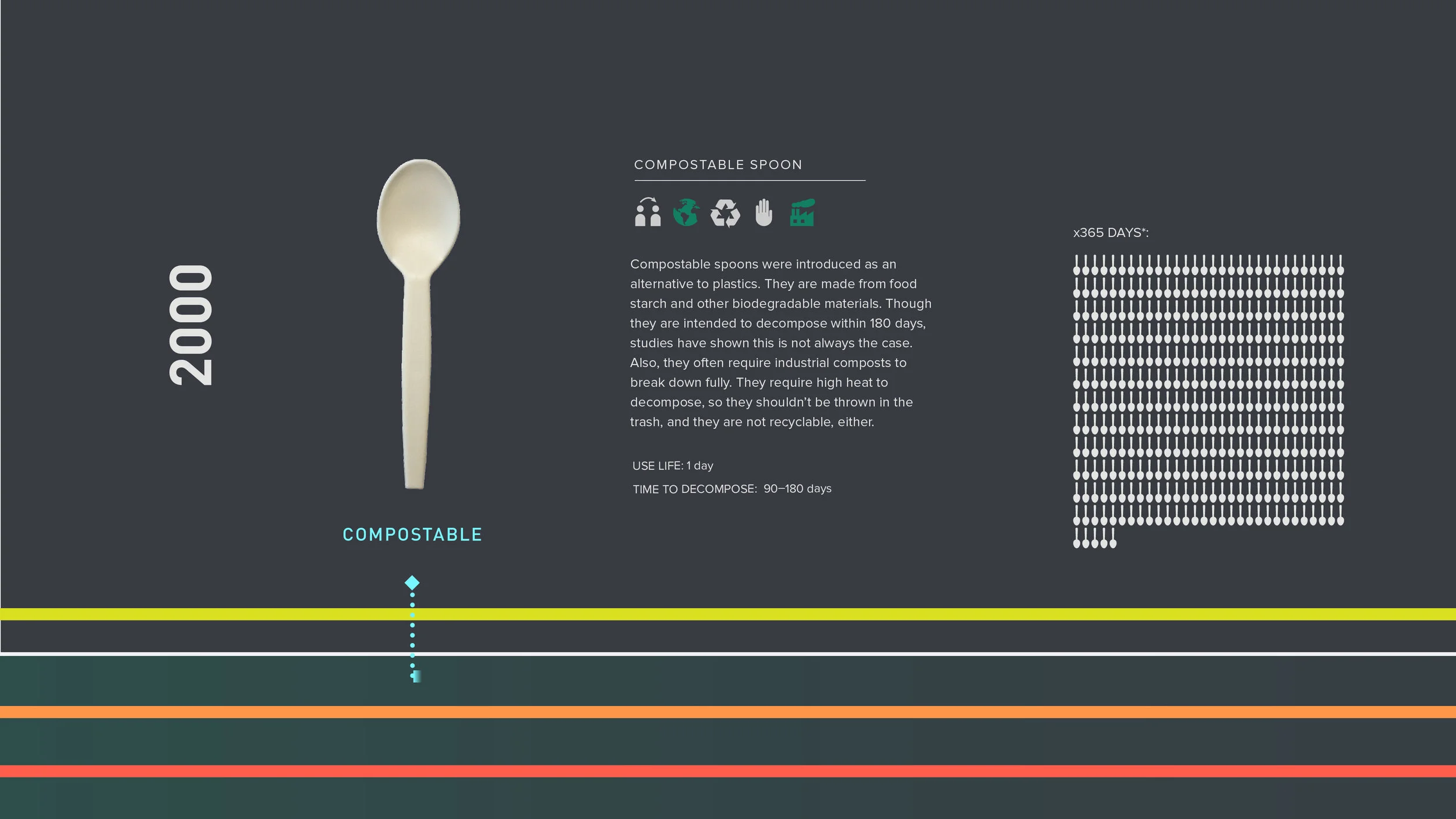

Mark Baskinger’s thoughts about disposability—that we use a plastic spoon for an hour and then it persists in a landfill forever—resulted in my adding the use life and decomposition time bars at the bottom of the timeline. His feedback during check-ins showed me that sustainability is more nuanced than we think, and that introducing that nuance allowed for a richer discussion about consumerism.

When speaking with Francis Carter, he raised the idea of considering heirloom objects in the timeline. He also suggested I visualize how disposable spoons accumulate over the course of a year, versus a single metal spoon which lasts a lifetime.

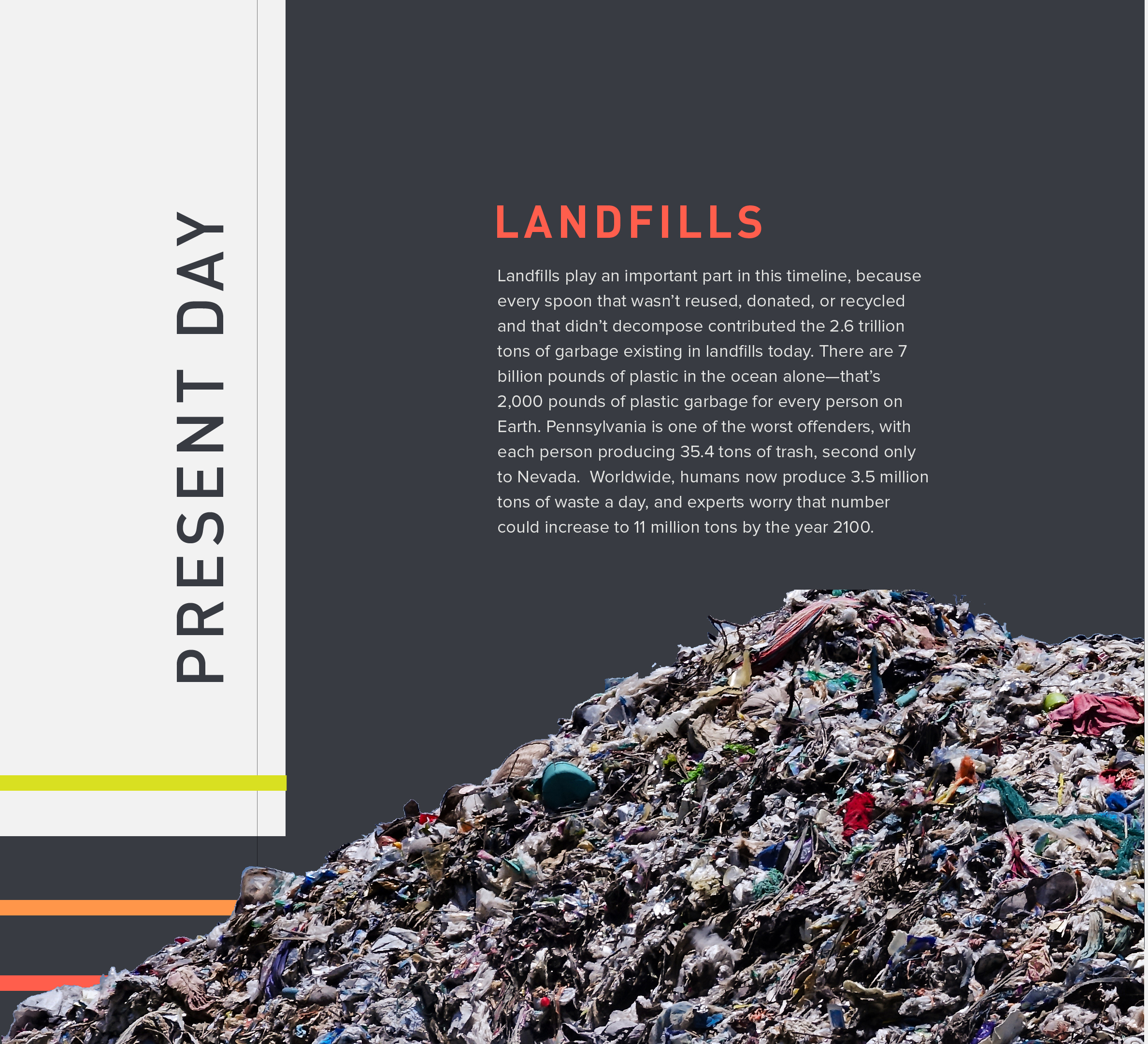

Finally, a photojournalism Washington Post article called “Drowning in Garbage” was so powerful and disturbing to me that I knew I had to include a landfill as part of the timeline.

FINAL CONCEPT

After thinking about and discussing all these different aspects of materiality, I wanted to be able to raise as many of these concerns in the consciousness of the users as possible. I decided to present the change in consumer habits through a spoon by using a timeline—thinking about how objects were made, used, and disposed of before modern technology and today, and how the change in consumption habits impacted the earth. To take this one step further, I wanted viewers to "design their own" artifact for the post-Anthropocene era. In so doing, users would be forced to reflect on the issues raised in the timeline, recognize their role in the Anthropocene, and empower them to design a better future.

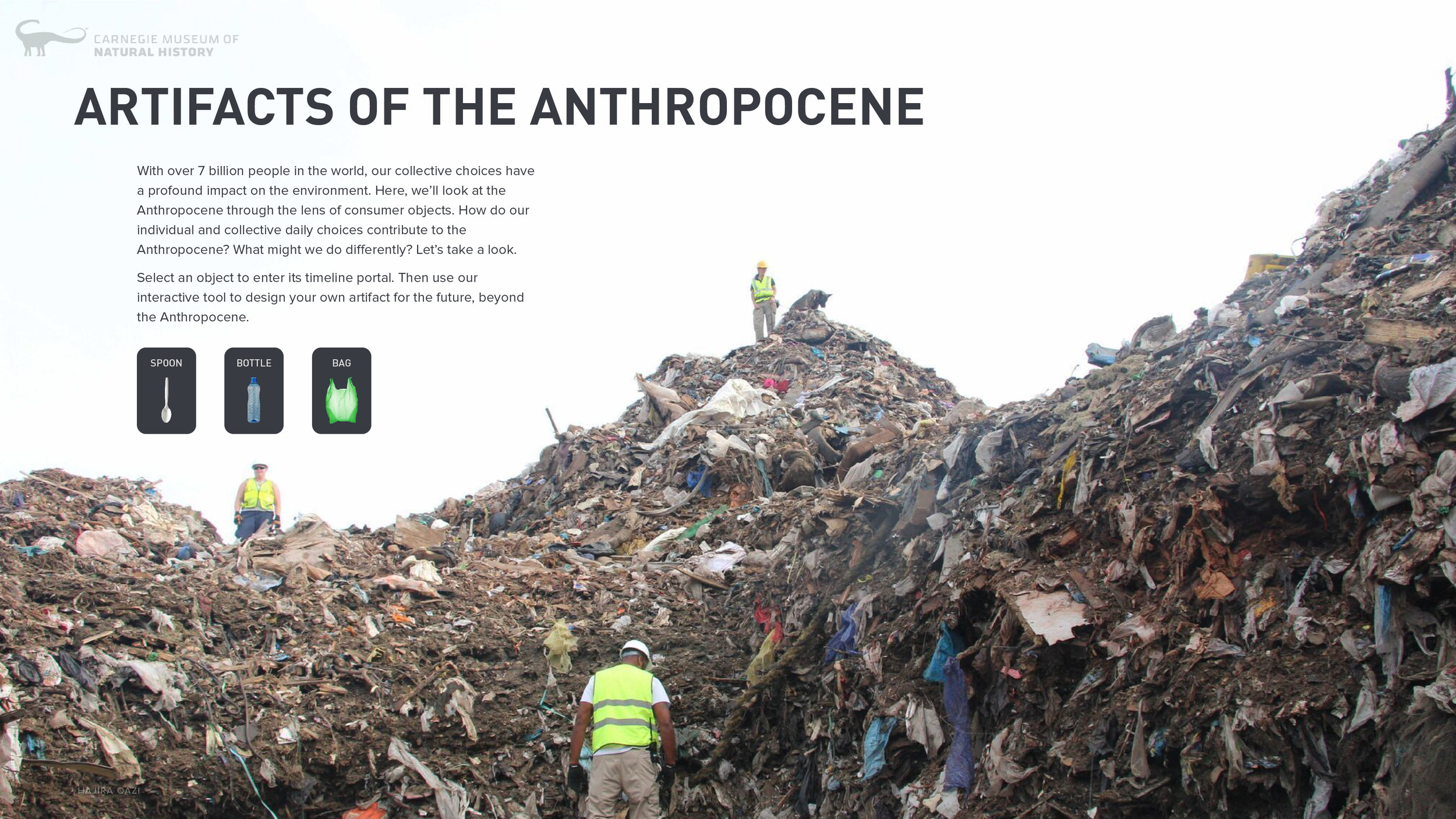

HOME PAGE

Users select on an object (spoon, bottle, bag) to enter a timeline portal for that object. I chose these objects because they are everyday objects the vast majority of the population uses in large quantities, but may not reflect on the impact they have. For this project, I built out the timeline for the spoon.

"Artifacts of the Anthropocene" is a play on words—in the design world objects are referred to as artifacts, but artifacts can also mean remnants of a particular period of time. The image of the landfill is a powerful visual of the remnants of modern consumption habits and the artifacts we leave behind for future generations.

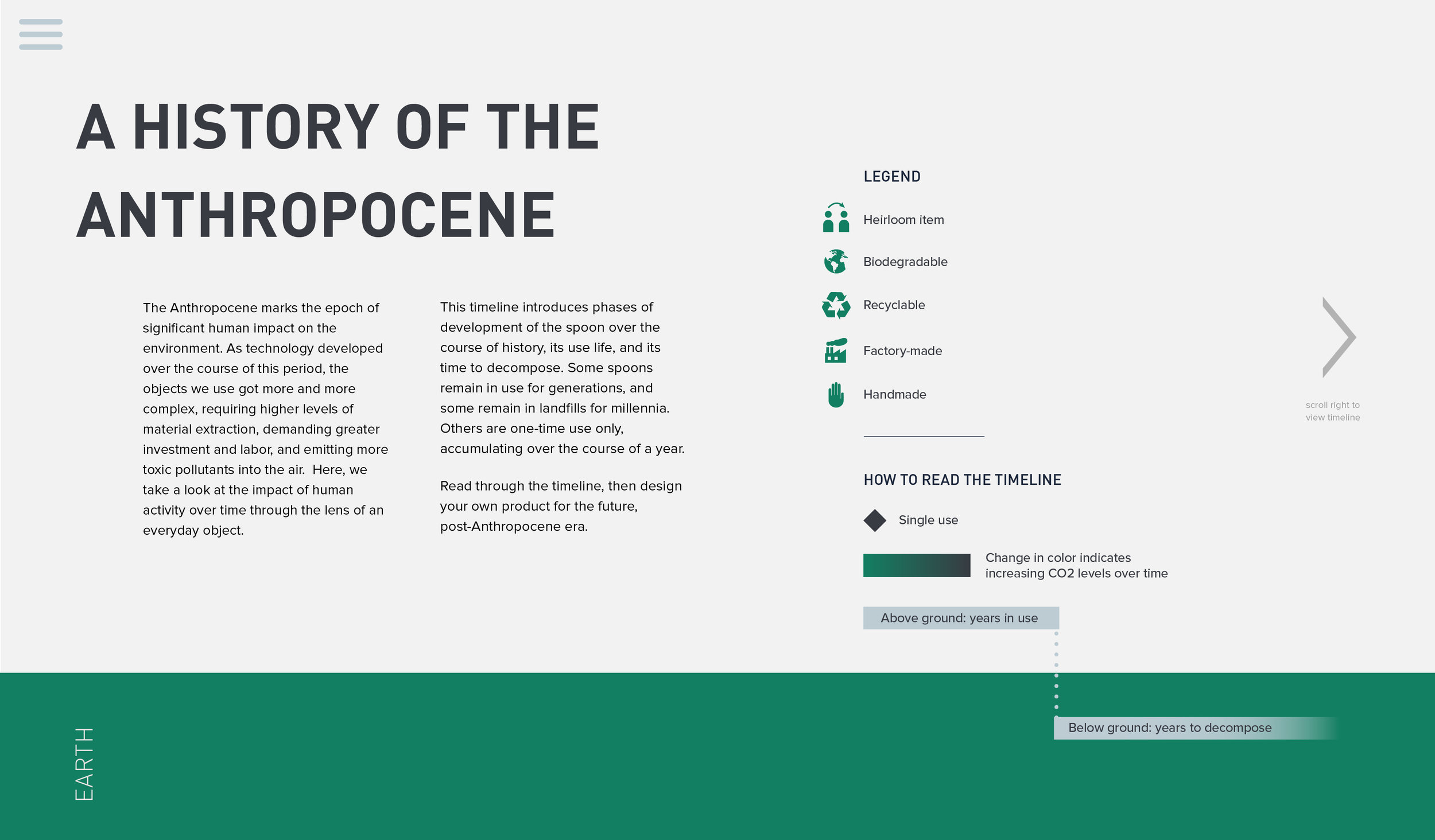

TIMELINE

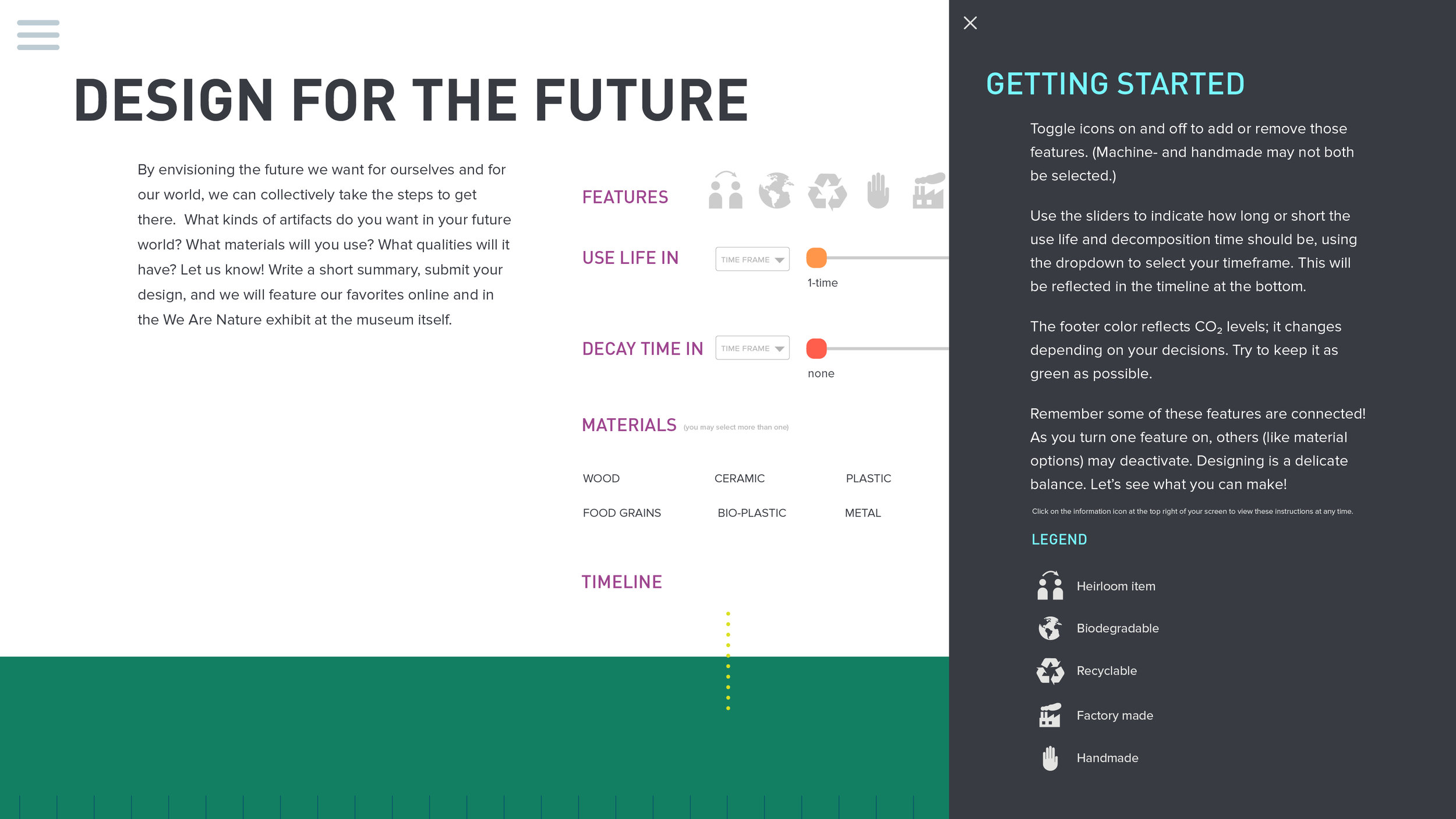

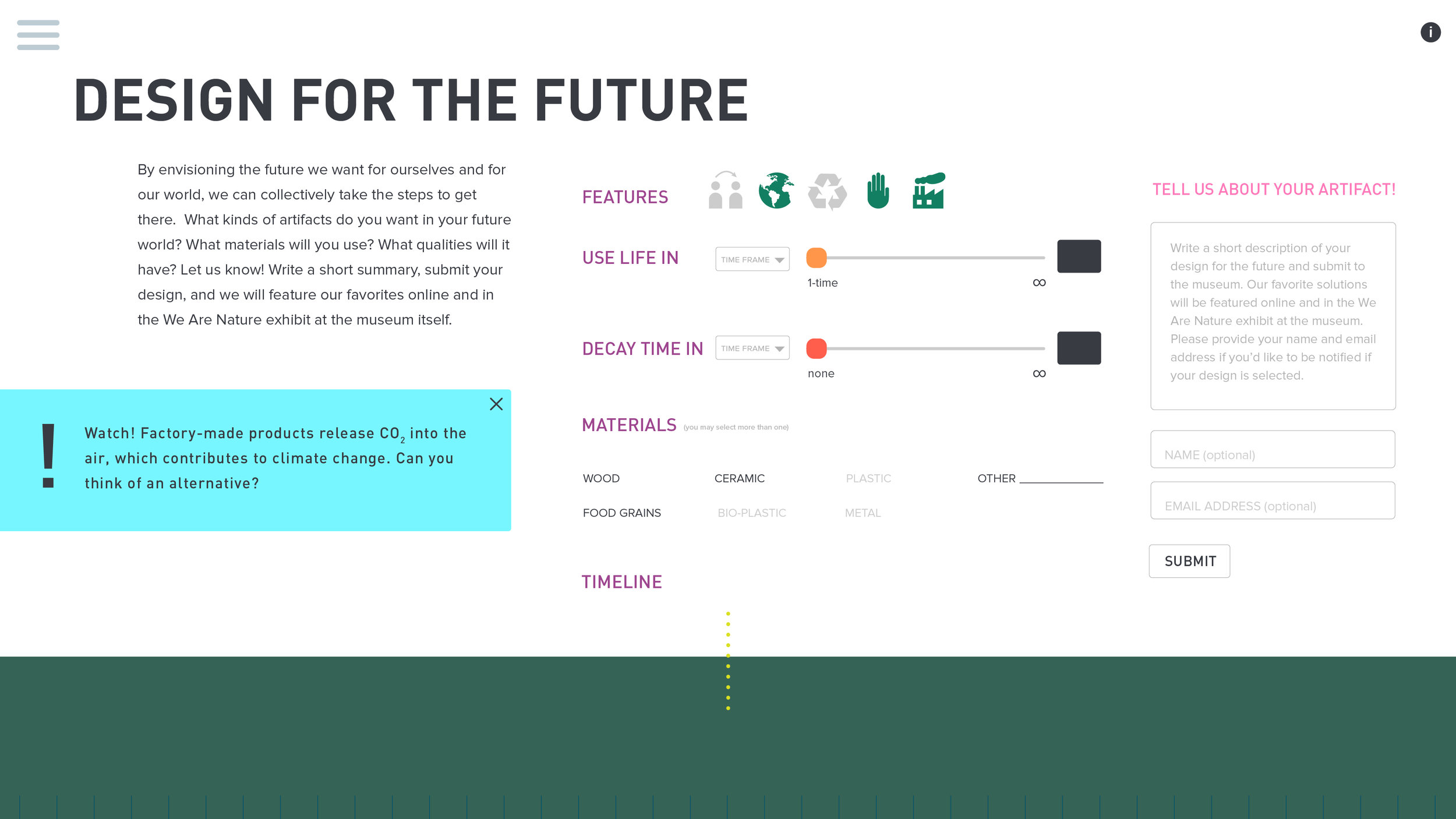

Among a long list of different aspects of materiality that came up during my research, I picked out the ones that relate most to consumerism. The ones that could be identified by “yes or no,” I converted to icons. Although handmade and machine made are two sides of the same coin, I thought it important to display both, to raise the concept of alienation in people’s consciousness.

The change in color of Earth (represented by the green bar at the bottom) reflects CO2 levels to communicate the change in the earth over the course of history. It also demonstrates how the changes were subtle but also sudden.

Showing the use life and decay life visually in terms of colored bars allows for relative comparison: how long am I using this, and how long does it persist on Earth? The bars that remain in "Earth" for a long time crowd up and lead to a landfill. The actual times are also written in the descriptions for users to see more specific metrics.

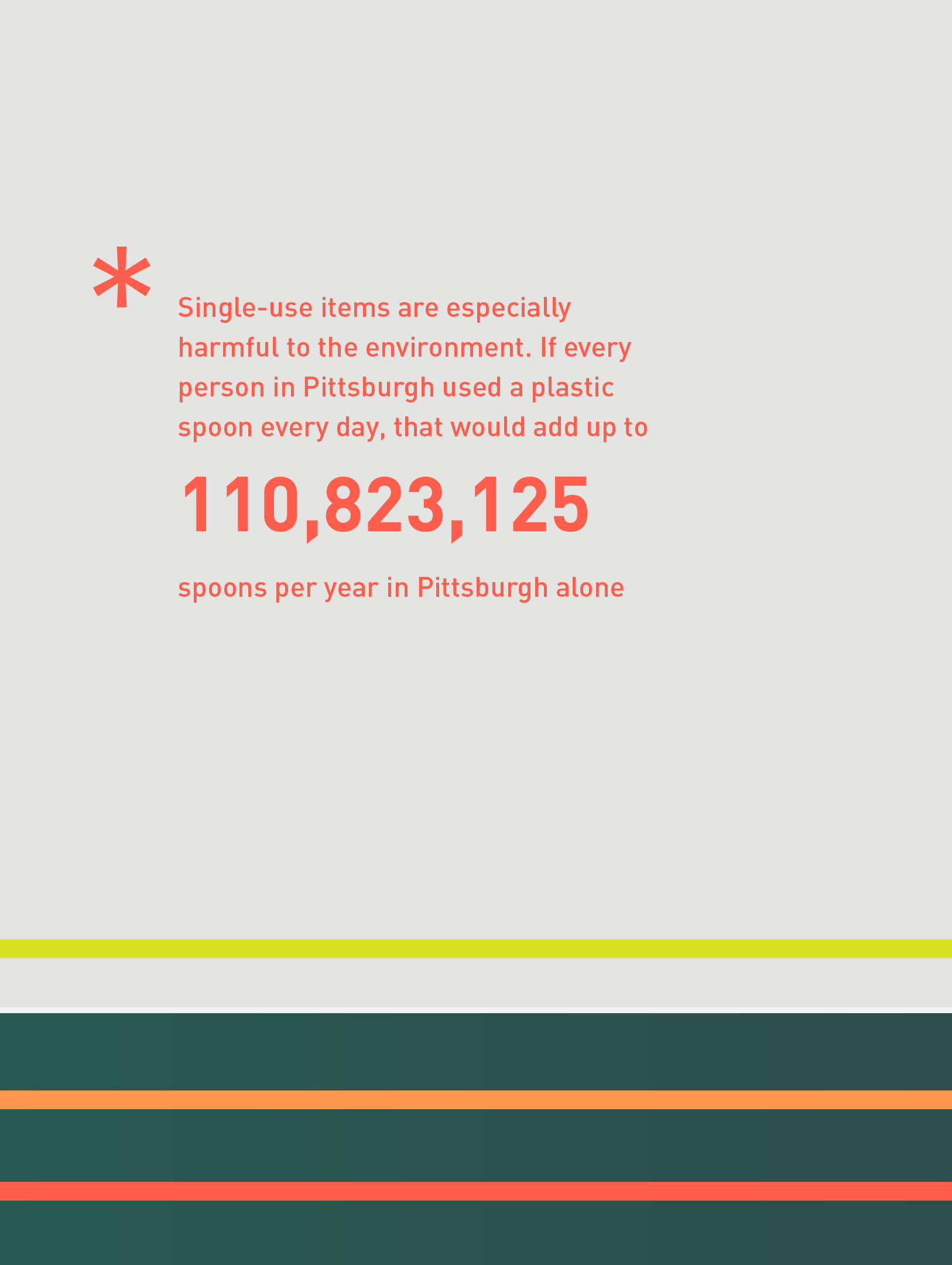

Communicating the number of spoons that get used over 365 days is another visual representation of how disposable objects accumulate over time. Multiplying by the entire population of Pittsburgh makes that even more clear.

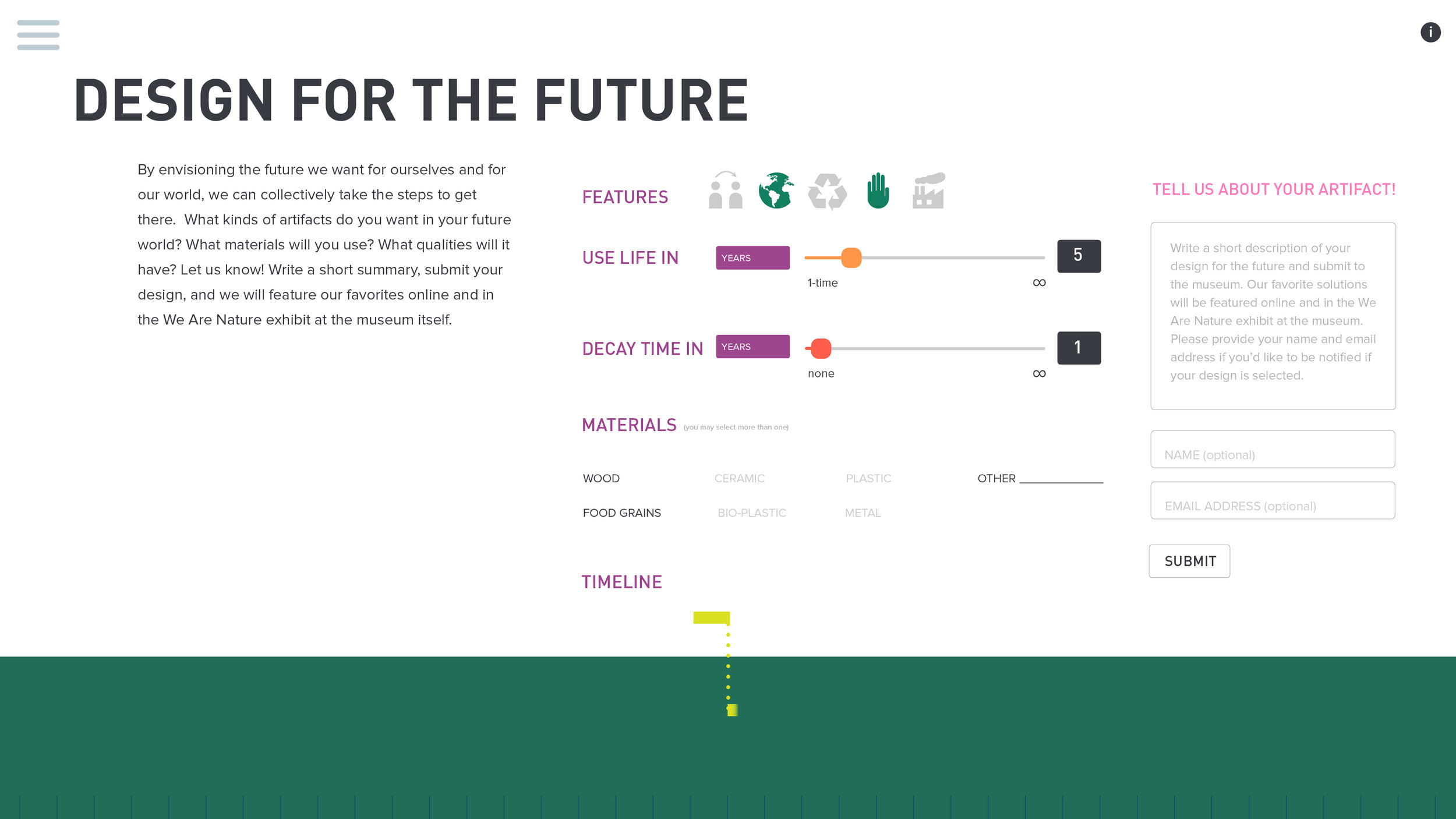

DESIGN YOUR OWN

It was important to me that this interaction not end on a low note such that users feel overwhelmed and depressed. I wanted to empower users to take what they learned from the timeline and do something good with it. So the final stage of the interaction asks users to think about the future they want, and to design their own artifact for the post-Anthropocene world. Designing one’s own artifact of the future helps to connect users to the future and make them invested in finding ways to improve it.

This is the most important element of the interaction, as it is what helps people translate what they learned through the timeline into action. When designing, they are forced to consider factors like biodegradability, use life, materials, and the overall impact those decisions have on the earth in terms of the changing color of green. They learn that there is no easy answer; it’s not just a matter of extending use life and reducing decay life, because the materials options also deactivate based on other factors. Users are alerted if their decisions are not sustainable or contribute to the degradation of the environment.

I realize these factors are only one part of the story, and there may be other options users would want that are not listed here. For this reason, I provided an option to add a description to support the design. By offering to feature the best designs in the museum and online, users are encouraged to be creative to find the best solution for the future.

FINAL SCREEN

The final page allows for advocacy by allowing users to save their reports and to share their ideas on social media. Recognizing that simply designing an object is not enough, there are additional suggestions for changing consumer habits to have less impact on the earth. These suggestions intend to drive home considerations like shortening the supply chain, reusing or donating items instead of throwing them away, and investing in products that last long.